Bigotry: The Dark Danger

The Microworld Miracle

DOWNLOAD THE BOOK

CHAPTERS OF THE BOOK

< <

8 / total: 9

One of Evolutionists’ Gravest Dilemmas: Insects

The preceding chapters examined the extraordinary abilities of microorganisms, their complex structures too small to be seen with the naked eye, and the invalidity of evolutionist explanations. But insects are even more interesting than microorganisms, and present just as great a dilemma for the theory of evolution. Insects occupy a very different niche than other species. As the fossil record shows, insects have been around for at least 400 million years. Over that time, various catastrophes have taken place, and large numbers of animal species have become extinct. Insects are among the few living things not to have been affected. With their superior creation, they have spread and multiplied in every kind of environment—deserts, forests, lakes, volcanoes, water, even icebergs, and in short, anywhere at all.

Some insects prevent their bodies from cold by producing a form of antifreeze. This lets them live on the high peaks of the Himalayas, while others endure temperatures above 47 °C in the Sahara Desert. There are so many species of insects that scientists cannot come up with an exact figure. Insects constitute three-quarters of all the animal species known today. According to the latest research, the total number of insect species is between 2 and 30 million. Only 370,000 of these have been described so far. Also, moreover, up to 15.000 species of fossil insect have been found. Their total numbers are estimated to exceed 1 trillion and their total weight, 2.7 billion tons—a figure equivalent to 45 billion human beings. In other words, there are more than 170 million insects for every human being.113 As you can appreciate from these extraordinary figures, insects also constitute a major link in the food chain. The Creation In Insects

The Carapace

Flight Systems

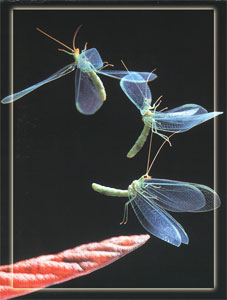

Some species have only two wings, and others four—and grasshoppers have two wing casuings in addition! Some beetles' wings fold inwards and have a protective casing; others have membranous wings, and others, like butterflies, ones covered with microscopic scales. Every type of insect wing exhibits its own unique perfection. Their wing joints are made of a special protein called resilin, which has perfectly elastic properties. Chemical engineers are still trying to produce this substance, whose features are far superior to those of both natural and man-made rubber. By means of stretching and contracting, resilin stores and can give back as much as 96% of the energy loaded onto it. Thanks to this, some 85% of the energy an insect expends in raising its wing is used again when it lowers the wing. The insect's chest walls and muscles have also been created to permit such energy storage. This allows extraordinary energy to be released, making it possible for insect wings to beat between 200 (for honeybees) and even 1,000 times a second (in sand flies). 114 Evolutionists suggest that some of the chitin layers in the insect's thorax turned into wings. They must know how weak that claim is, because they also state that there is no fossil to verify this. Various scenarios have also been produced to explain how insect flight evolved. According to the so-called tracheal theory, when insects living in water emerged onto land, they developed wings from the trachea in their thoraxes. The invalidity of this theory was revealed the moment it was unveiled, because the same muscles found in aquatic insects' gills are not found in wings. Furthermore, there is no evidence of transitional fossils to show that insects went from a wingless phase to a winged one. On the contrary, fossils reveal no "primitive" insects. Even the oldest known insects had the same perfect flight systems as those living today.

The second scenario, the so-called paranotal theory, maintains that certain regions in the thorax expanded, flattened out and gradually assumed the form of wings. According to this claim—for reasons unknown to evolutionists—only two of the three sections in insects' thoraxic regions exhibited this alteration and thus gave rise to wings. One can see a similarity in the way that evolutionists seek to account for bird flight. However, elements in both scenarios make them invalid and illogical. The most important of them is that the fossil record invalidates these claims. Secondly, wings possess irreducible complexity: they function only if they exist as an entire unit. The half-wing or newly emergent wing suggested by evolutionists would be worse than useless. Third, in genetic terms, no mutations that can add new beneficial features to a species or improve already existing ones. For that reason, if a flight system were not already determined in a creature's DNA, it is impossible to add new "flight-worthy" data to that DNA via random mutations. In other words, blind coincidence can produce no new information in nature. In order for an organ like a wing or an eye to form, there needs to be a Supreme Creator. Yet there is no such consciousness in nature. In any case, evolutionary scenarios tend to cite the world view imagined by the person drawing up the scenario, rather than scientific details. Ideological obsessions weigh heavier than facts in the shaping of these conjectures. The well known French zoologist Pierre Paul Grassé admits the truth of this in the words, "We are in the dark concerning the origin of insects." 115

In fact, however, that the flawless creation in the fly wing invalidates all claims of chance. In an article published in the journal Scientific American, Robin J. Wootton from Exeter University comments on insects' flying abilities: Insects include some of the most versatile and maneuverable of all flying machines. … some insects-through a combination of low mass, sophisticated neurosensory systems and complex musculature-display astonishing aerobatic feats. Houseflies, for example, can decelerate from fast flight, hover, turn in their own length, fly upside down, loop, roll and land on a ceiling-all in a fraction of a second… The better we understand the functioning of insect wings, the more subtle and beautiful their designs appear. Earlier comparisons with sails now seem quite inadequate. The wings emerge as a family of flexible airfoils that are in a sense intermediate between structures and mechanisms, as these terms are understood by engineers. Structures are traditionally designed to deform as little as possible; mechanisms are designed to move component parts in predictable ways. Insect wings combine both in one, using components with a wide range of elastic properties, elegantly assembled to allow appropriate deformations in response to appropriate forces and to make the best possible use of the air. They have few if any technological parallels-yet. 116

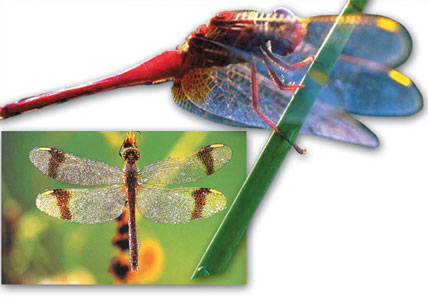

Look at the dragonfly, which evolutionists describe as "more primitive" compared to other insects, and it becomes apparent just how ideology-oriented such claims are. Dragonflies cannot fold their wings, the way their muscles cause the wings to move is different from that in other insects. Solely on account of these features, evolutionists claim that dragonflies are "primitive." Yet the dragonfly's flight system is actually a marvel of creation. Leading companies have produced helicopter models in imitation of this flight system. Photographer Gillian Martin undertook a two-year study aimed at investigating dragonflies, and the information he obtained showed that these insects possess very sophisticated flight systems. The dragonfly abdomen gives the impression that it's covered in chain mail. Its two pairs of wings are located diagonally on top of its thorax, whose colors of which range from ice blue to burgundy. Thanks to this wing structure, the dragonfly has considerable maneuverability. No matter what its speed and direction of flight, it can suddenly halt and reverse course, or else hover in the air, waiting for an appropriate moment to attack its prey. It can also approach its prey by making a convoluted, curving approach. It can quickly reach a speed of 40 kilometers (24,85 miles) an hour— quite astonishing for an insect—at which rate it seizes its prey.117 The shock of the impact is very strong, but the dragonfly's exo-armor is both very strong and very flexible. Its flexibility absorbs the shock of the impact, even though the same cannot be said for its prey, which is either stunned or killed.

The dragonfly's visual ability is also flawless. The dragonfly's eye is regarded as the best insect eye in existence. Its two eyes each possesses around 30.000 lenses.118 These hemispherical eyes cover most of its head, giving the insect a wide field of vision. Thanks to these eyes, a dragonfly can almost a good deal of what is going on behind it.

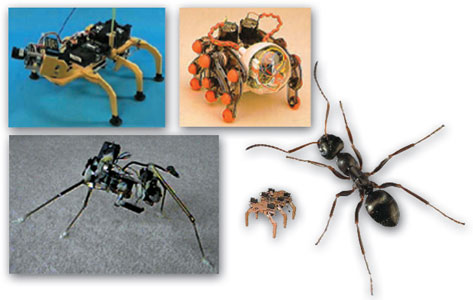

FeetThe feet of ants and bees are surprisingly complex structures, says Brainerd. Each foot, viewed through a microscope, has a pair of claws that resemble a bull's horns, with a sticky footpad called an arolium positioned between the claws. When the insects run along a surface, she explains, the claws try to grasp the surface. If the claws are unable to catch onto the surface, they retract and the footpad comes into action. The footpad quickly unfolds and inflates with blood, protruding between the claws and enabling the adhesive pad to stick to the surface. The footpad then deflates and folds back. The entire process takes just tens to hundredths of a second, and is repeated with each step, rapid-fire, as the insects skitter along. In addition, the footpad secretes a fluid that allows the insects to adhere to smooth surfaces, "the same way a wet piece of paper can stick to a window," says Brainerd. The dynamic nature of the arolium provides varying levels of stickiness, depending on the surface. 119

The researchers also discovered that the tendons controlling the claws are responsible not only for retracting them, but also for moving the feet pads. This system is a perfect combination of mechanical and hydraulic systems. By imitating these systems, manufacturers are working on the production of miniaturized robots to be used in medicine.

Antennae

Insects' antennae, which also impart a pleasing aesthetic appearance. makes these invertebrates creatures aware of what is going on around them. Their antennae perceive and analyze the chemicals they use to communicate with one another by. Although antennae are sometimes regarded more as feelers to augment their sense of touch, their basic function is to provide the insect with a sensitive sense of smell. A large number of olfactory nerves are arranged along the antennae, and these detect the aromas of foodstuffs and identify the chemical messengers or scent-bearing molecules known as pheromones belonging to the opposite sex. Communal insects like ants and bees, also used their antennae to establish identity and for chemical communication. They analyze the chemical signals released by others by touching them with their antennae and determining whether they are friends or foes. Mosquitoes can perceive sounds through their antennae. When one examines the countless features of insects, such as their sensitive antennae, the chemicals they use to communicate, their bodies created like robots, the resistant structures that permit them to live under all kinds of conditions, the poisons they use for attack and defense, the way they enter into shared lives with other living things, the exquisite tissues of some insects such as butterflies, metamorphosis, hunting and tactics like camouflage, a very broad, complicated picture emerges. These properties, the subject of whole libraries of books, yet they actually represent the very limited knowledge we have of insects. There are hundreds of thousands of insect species that have not yet been discovered or described, each has its own separate structures. Even the best-known and most studied insects possess amazing properties.

For instance, some of the most widely studied insects such as ants, bees and termites, possess exceedingly developed social systems, and releasing various chemical compounds to communicate. They organize themselves to establish division of labor in their colonies. They can construct nests like miniaturized skyscrapers and perfect honeycombs. Such species of ant engage in agriculture and sewing, and some solitary bees practice pottery. Communal bees produce honey and beeswax in their hives. Some other classes of insects undergo metamorphosis. A caterpillar that eats leaves emerges from its chrysalis as a brightly colored butterfly. Silkworms produce threads used in clothing. Grasshoppers and fleas are prodigious jumpers. Fireflies produce their own cold light in the most economical manner. Some insects live symbiotic lives with plants or even with other insects. Insects display astonishing properties of speed, flight, leaping and running. When it comes to these special attributes, only a few of which have been listed here, evolutionists, who cannot even account for the origins of insects in general terms, can go no further than repeated their time-worn explanations creations. Insects' Fascinating Behavior

Looked at from the point of view of evolutionary mechanisms, insect behavior assumes a whole new significance. These forms and properties of insect behavior refute the fundamental mechanisms of evolution. As touched on briefly earlier, the most advanced behaviors are seen in insects that live as one social organism. It is impossible for evolutionists to trace the specific development of these forms of behavior. For that reason, they examine each behavior individually, and then try to account for it within the framework of evolutionary logic . Efforts of this sort mean a new evolutionary tall tale for each different behavior. Professor Ali Demirsoy, a well known Turkish evolutionist, makes the following comments: In every phase of a living thing's life cycle, many forms of behavior unique to its own species regarding natural conditions, and the other living things in its habitat, can be seen ... All this behavior can be based on specific physical and biological laws. However, it is impossible to account for it all in the present state of our biological knowledge.120 The objective of biology is to study animal behavior, discover the neurological, chemical and biological factors that cause it, and to reveal the results with concrete evidence. However, seeking to fit behavior into the evolutionary scenario without any evidence is not science, but an application of ideology. Yet in the examples just cited, you can easily see that, like the behavior of other animals, insects' habits did not emerge as a result of a gradual process of random evolution, but was created as an ideal whole.

We encounter the most fascinating behavior in insect colonies. A large ant colony functions as a single organism, with complete order and discipline. Ants communicate by means of pheromones, of which scientists believe there are two varieties. The first has general effects, and the second applies to immediate effects such as alarms. Members of one colony are distinguished from strangers by their unique scent. Every ant has a specific duty in the colony. Right from the moment it hatches from its cocoon, each ant performs its duty to the letter. One most interesting feature of this superior organization is how an ant is ready to sacrifice its life without hesitation in the event of danger to the colony. Even ants that have been injured or lost a leg or antenna do not turn and run away. Some ants become living bombs, inflating their acid sacs and blowing themselves up in the midst of their enemies. In addition, some species of ants steal pupae from other colonies and use the ants that hatch as slaves. The engage in agriculture by growing fungi in particular chambers of their colonies, or by raising other aphids whose secretions fluids they drink. They enter into symbiotic relationships with plants or other animals, and even sew, stitching leaves together for their nests. Bee and termite colonies also display unique forms of behavior. Honey bees construct perfect combs that display their architectural abilities. Besides using pheromones, they also communicate by means of the so-called bee dance. The self-sacrifice displayed by ants is also observed in bees. Whichever insect species we examine, you can encounter a different system of behavior. While ants take other insects prisoner, some insects live as parasites in the other insects' colonies by imitating their scent. Some insects even live by stealing food belonging to others. All these features reveal one fact in total clarity: Insects, which have been living for hundreds of millions of years and come down unchanged to the present day, completely refute the theory of evolution. To understand this more clearly, simply compare insect behavior with the mechanisms proposed by the theory of evolution. The Primitive Insect Fallacy

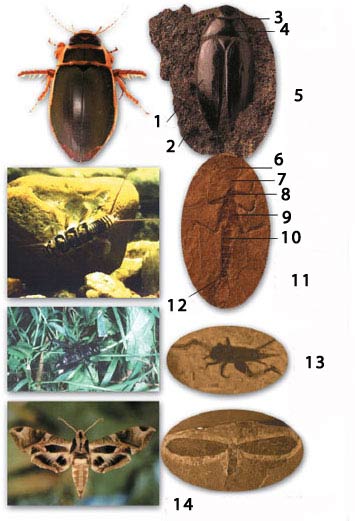

As with dragonfly, evolutionists tend to interpret very ancient fossils as "primitive." Their true aim is to insert insects, with their complex structures that fail to fit any evolutionary scenario, into an appropriate gap in the evolutionary framework. Cockroaches, interpreted from that evolutionist perspective, are just as primitive as are dragonflies. In fact, close examination of the cockroach reveals the kind of complex structures seen in the dragonfly. It is true that the cockroach fossils dating back 350 million years have been found. But rather than proving that cockroaches allegedly evolved, these fossils actually demonstrate that cockroaches were created. There is absolutely no difference between fossils that lived in those times and present-day specimens: cockroaches have undergone no changes over the last 350 million years. Far from having a primitive structure, these insects have managed to survive conditions that most living things could not, down to the present day. In addition, cockroaches possess complex structures encountered in all insects: Highly developed antennae, the body-covering chitin, and the perfect wing structure are all present. They have eyes made up of some 2.000 lenses, a mouth and jaw structure ideal for consuming all kinds of food, rather resembling highly advanced scissors. Their feet enable them to walk on all surfaces, and they are sensitive to all types of external stimuli such as pheromones, heat, vibrations and light intensity. With these exceedingly complex structures, cockroaches are not a primitive species, but the product of an supreme creation.121 Each of a cockroach's features has been created and brought together for a specific purpose; and each possesses irreducible complexity. They can serve no purpose unless they have emerged all at once, and fully formed. A too-short antenna or a foot able to cling to surfaces only some of the time will lead to the death of the insect. For that reason, an animal's organs must either be entirely developed as a whole or not at all. This rule applies to all other living things.

The same creation applies to the first known insect, Rhyniella praecursor. This fossil, belonging to the springtail class, is around 396 million years old.122 However, these insects—of which more than 3,500 species are alive today—are by no means simple, as evolutionists fondly suppose. On the contrary, this insect's advanced structure enables it to live everywhere in the world, at the Poles, on water and even in the depths of the earth. Springtails take their name from a special fork-shaped structure at the tip of their tails that normally curves forward over the body. The stem of the fork is fixed by another structure. When the muscles rapidly propel this fork backward, it strikes the ground and lets the insect make long leaps and escape danger. It can even jump on water. Springtails are of great use in breaking down and plowing the earth. They possess very complex mouth and jaw structures for tearing, masticating and sucking. On their body surfaces are structures known as pseudocels that squirt out fluids at moments of danger. In addition to the advanced antenna in other insects, they also have what's known as a "postantenal" organ, peculiar to this insect alone. Scientists believe it serves to perceive moisture. Air cushions between its hairs are used for breathing in aquatic environments. Some species can emit light from their bodies, and also perform a special mating dance.123 The springtail, which evolutionists describe as primitive, has perfect structures and highly developed organs and mechanisms. Far from being primitive, Rhyniella praecursor is a perfect insect that cannot be distinguished from present-day specimens. Like the other examples cited above and distorted by evolutionists in order to portray them as primitive, this insect emerged not as the result of imaginary coincidences but as the product of creation. In other words, these creatures too were created by Allah, Lord of the heavens and Earth and all that lies between.

Insects Argue Against Evolution

A major problem for the theory of evolution is that insects emerged suddenly in the Devonian and Upper Carboniferous periods, in their present-day forms. The primitive ancestor of all insects is nowhere to be seen. In other words, insects did not emerge by evolving from a more primitive entity, but emerged around 350 million years ago in their present-day forms and possessing the same complex organs, and never underwent evolution. Fossils have been found belonging to 69% of the 1.087 families of insects known today. All these fossilized insects have the same features today—one of the problems that evolutionists are unable to resolve. 124 Their second major problem is the sheer variety among insects. According to the evolutionary scenario, there should be a limited number of insect species, all descended from the same forerunner. However, the actual number of insect species is estimated to exceed 30 million. Such an enormous number of species represents another question that evolutionists are unable to answer. There is not enough time for an imaginary process such as mutation to give rise to such variety. In their book An Introduction to the Aquatic Insects of North America, Prof. R.W. Merrit and K.W. Cummins from California Berkeley University comment: Interpretations of the fossil record must be made with great caution. For example fossils used in evaluating the terrestrial aquatic origin of insects were recently found to be not primitive insects at all, but merely fossilized segments of crustaceans!125 Despite the large number of evolutionist scenarios about the origin of insects, scientists who closely research the subject arrive at these same conclusions. But proponents of the theory of evolution do not base their arguments on concrete evidence. The comments by H.V. Daly and J.T. Doyen of Berkeley and Oxford universities make this clear: Unfortunately, evidence of the crucial steps leading to the origin of insects have not yet been found in the fossil record. Wings have contributed more to the success of insects than any other anatomical structures, yet the historical origin of wings remains largely a mystery. The earliest insect fossils that have been discovered, from the Pennsylvanian Period, were already winged . . . Thus the body structures that developed into wings, the steps in the evolution, and the ecological circumstances that favored wings are debatable. 126

In a paper published in Nature magazine following long years of research, Ward Wheeler of the American Museum of Natural History also emphasizes the lack of evidence and states that the work failed to deliver Darwinists' desired results: "You can never be sure that you have the right answer, because each group's origins are lost in the mists of time." 127 Another major problem is that insects' exceedingly developed structures—their wings, and abilities of chemical communication, social organization and architecture—cannot be accounted for in terms of gradual evolution. Such fictitious mechanisms as useful mutations do not exist in nature. As these examples show, insects have been specially created and equipped with superior abilities to perform their duties on Earth. The "Common Evolution" Scenario

The proponents of evolution have always experienced grave difficulty in explaining the close relationship between insects and plants, the vital links between their shared lives and the great range of plant-insect interactions. As you know, insects suddenly appear in the fossil record, with no primitive forerunner behind them, and this applies to plants as well. In particular, fossils from 43 different families of flowering plants, which make the greatest use of insects, appear suddenly in the fossil record. There is no question of any intermediate form or primitive ancestor. Yet according to the mechanisms of evolution, such a wide variety of plants should have left behind millions of intermediate-form fossils of relatively primitive ancestors. However, even though fossils of most living species have been found, no such primitive or transitional fossils have ever been found. Lack of evidence is a familiar dilemma for evolutionists. Since they are prepared for such situations, proponents of the theory have made a habit of speculations and scenarios. In employing this unscientific method, the existence of proof is irrelevant. Advocates take the mechanisms of evolution as a starting point, and describe events as they imagine they should have been, rather than as they were.. Then, even though all the evidence argues against them they seek to make a reality of that fairy tale. However, it is easy to ask just the right questions in order to understand the fraudulent nature of those defenseless scenarios. The insect species involved in the claim of joint evolution are the Coleoptera, or beetles—a very numerous group, constituting approximately one-third of the insect classes. They derive their name from their two pairs of wings. The front wings are hard and contain chitin, which makes them like protective shields. They also help maintain balance during diving and flight. The rear wings provide flight. After completing its flight, a Coleoptera insect closes its wings, with the hind wings beneath the front ones. The way the protective front wings cover the rear ones is a separate marvel of engineering. Thanks to their ability to fold their wings in this manner, they can enter even the smallest holes, without harming their flight wings in any way. And these insects emerged at least 350 years ago, suddenly and in full possession of this perfect creation!

Insects like bees and butterflies, which pollinate flowers, also appear suddenly in the fossil record and have come down to the present day with no changes since they were first created. Bees that lived 150 million years ago also constructed the same perfect combs and produced honey. The theory of evolution claims that the first flowering plants emerged and multiplied some 150 million years ago, and certain insect species entered into a relationship with these plants and also emerged and multiplied. At first glance, this scenario may seem to account for the origins of plants and insects. But the facts are not as simple as the evolutionist scenario would have you believe. The essential questions remain unanswered: Flowering plans and their pollinating insects appear suddenly in the fossil record. According to the theory of evolution, there should be not only a common ancestor, but countless intermediate forms between that ancestor and the species' final form. In such a rich fossil record, why has not a single one ever been encountered?

The proponents of evolution tend to generalize when referring to plant and insect variety, as if they all had the same features. Yet every insect and every plant possesses unique structures that distinguish it from every other. For instance, bees, butterflies, ants, leaf mites, locusts, cockroaches, fireflies, mole crickets, and fleas are all insects, yet display totally different features that represent more unanswered questions for evolution. The proponents of the theory set about preparing a general scenario for each of these, even though they were still unable to account for the origin of any living things, their complex structures or their social behavior. Yet evolutionists really must be able to account for the origin of every separate species of insect, and of the every feature they possess. In doing so, they must act in the light of the scientific facts, rather than of outdated ideologies or conjecture. Adherents of the theory of evolution often interpret variations within a given species as an entirely new species. That is one of the greatest distortions made in the name of evolution: the claim that mutations or environmental factors cause brand-new species to come into being. Another is that with the appearance of flowered plants, the suitable conditions they offered led to the emergence of new species of pollinators. This claim too is also full of internal discrepancies and distortions.

In order to better understand this problem, we first need to nail down the meaning of the concept species. The word tends to bring to mind unique types of plants and animals such as horses, camels, frogs, spiders, dolphins, palm trees and roses. The theory of evolution posits a common origin of these various organisms. Yet modern biologists describe the concept of species rather differently. They define a species as a group of plants or animals capable of mating and reproducing among themselves. For example, some 40.000 species of bees have been described.128 In other words, in essence these 40.000 different bees are all different sub-species within the species of Apis. Genetic information belonging to the species permits various changes to take place within this species, but a bee can never turn into a butterfly because there are insuperable genetic differences between the two species. In biology, this rule is generally referred to as genetic homeostasis, the principle that all attempts to improve a living species remain within defined boundaries, defined by the are insuperable barriers between species. Changes within a single species are known as variations or sub-species. The same rule applies to plants. Efforts over hundreds of years have never given rise to a new species of plant. All that has occurred is that by manipulating that plant's existing genetic information, a range of observable variations have been allowed to develop. The Danish scientist W.L. Johansson summarizes the situation: The variations upon which Darwin and Wallace placed their emphasis cannot be selectively pushed beyond a certain point, that such variability does not contain the secret of "indefinite departure." 129

Looked at from that perspective, evolutionists' distortion can be seen more clearly. Plants and insects have not given rise to any new species by interacting with one another. Furthermore, the diversity in the present day is not the result of this variation. There is no question of there being any such evolutionary mechanism. The real question that evolutionists must answer is how a species such as the honeybee or the rose came into being in the first place. How did mammals, birds, and mollusks and their various classes, orders, and families first come into existence? It is by no means easy for Darwinists to answer these questions.

The known families of plants and insects were clearly created as works of art by a superior intelligence, suddenly, each in its own particular form. Each species has its own genetic pool. In the framework of this existing pre-programmed information, great many variations within the same species with very different attributes have often emerged. However, no cockroach has ever turned into a bee, nor an apple tree into a pumpkin vine. No mechanism in nature can design new types or form new organs and bodily systems for a new species. Each plant and animal form has been created with its own unique structures, and since Allah has created many of them with a rich potential for variation, each type has emerged with a rich but bounded variation. Accounting for the close interrelationships that appear between given plant and insect species has also become a problem for the theory of evolution. Very often, two entirely different species can survive only so long as they live together intimately, meshing their life cycles. As you saw in previous chapters, plants and insects emerged suddenly with their separate different structures. However, between some of them there exist relationships based on very sensitive interdependence. For example, the yucca moth pollinates the yucca's flowers and its larvae live only on the developing yucca seeds. These bees have been equipped with special structures that they may perform the pollination process. They have long mouth structures to sip nectar and hairs to which pollens adhere. Ants protect certain flowers, such as the acacia's, from harm and receive nectar in return. The butterfly species Xanthopan morgani praedicta assists in the pollination of the Madagascar orchid by extending its 28-centimeter (11.02-inch) long proboscis into the 28 to 30 centimeter (11.02- to 11.81-inch) spur of the flower. Some plants possess special traps for insects, and many insects eat plants; flowers and leaves. The relationship between plant and insect that evolutionists place no further back than 150 to 200 million years ago has been totally altered by one recent discovery. The latest fossils of structures known as galls, and one of the most basic relationships, show that this relationship between plant and insect has been continuing for more than 300 million years.130 During their developmental stages some insects are protected and fed in these structures, which form on the leaves and stems of certain plants. Gall formation is a miraculous system all of its own. The plant produces a tissue that enfolds the insect's larva and in effect, imprisons the insect. In this way, plants are protected from further harm caused by insects, and the insects' young find a roomy shelter where they can feed in peace. The insect in this phase prevents another parasite that uses certain secretions (beta indolic acid) from occupying the site. Even if the plant dries up, the cells that form the gall remains alive for a short while longer.

These relationships established between plants and insects have emerged as the result of creation. No plant possesses any information about a pollinator like a bee, butterfly, or hawk moth. In addition, it cannot know when it releases a scent that insects can perceive. Furthermore, the plant, being unaware which of scents will attract flies, cannot know that bees will kill the parasites that are feeding on it. There is no possibility of these mutual systems of behavior developing with minute changes over time, via unconscious evolutionary processes. Parasites will not permit the plant to analyze the bee's sensory apparatus and construct a means to produce the relevant attractive chemicals, and the plant will soon die before going to seed. This also applies to any systems affording mutual benefits. Unless a given system has been created as already complete and functioning, based on mutual behavioral and chemical balance, it will serve no purpose and have to evolutionary reason to survive. For example, in order for the eggs 28 centimeters (11.02 inches) down in the plant to be pollinated, the flower requires an insect with a proboscis 28 centimeters (11.02 inches) long, ever since that plant was first created. It has no time to wait for the long-tongued hawk moth, [Genus] predicta to evolve. The orchid would have died out unless both it and the hawk moth were created at the same moment. As with all the mechanisms and balances cited here, our omniscient Lord consciously and deliberately created these two species with a superior harmony and perfect features to enable each other. There is no creature crawling on the Earth or flying creature, flying on its wings, who are not communities just like yourselves–We have not omitted anything from the Book—then they will be gathered to their Lord. (Surat al-An‘am, 38)

Footnotes113- Zuhal Özer, Böcekler, Bilim ve Teknik, ?ubat 2000, sf.92 114- Kanatlı Böceklerin Uçuş Becerileri, Bilim ve Teknik Görsel Bilim ve Teknik Ansiklopedisi, sf. 2678 115- Pierre Grasse, Evolution of Living Organisms, Academic Press, New York, 1977, sf.30 116- Robin J. Wootton , The Mechanical Design of Insect Wings, Scientific American, vol.263, Kasım 1990, sf.114-120 117- http://www.southwestgardening.com/bugs/dragonfly.htm 118- Gillian Martin, Helikopter Böceği Acımasız ve Yırtıcı, Hürriyet Star Eki, 16 Ağustos 1984. sf.32-33 119- http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2001/09/010928071138.htm 120- Ali Demirsoy, Yaşamın Temel Kuralları Omurgasızlar -Böcekler Entomoloji, Cilt 2 /Kısım 2, Meteksan Yayınları, Ankara, 1984, sf.217 121- http://roachcom.net/inside 122- Encyclopedia of Life Sciences , "Insecta (Insects)", http://www.els.net/?sessionid=1061953ed85edf71 123- Ali Demirsoy, Yaşamın Temel Kuralları Omurgasızlar -Böcekler Entomoloji, Cilt 2 /Kısım 2, s.323-24 124- http://www.icr.org/newsletters/impact/impactnov00.html 125- http://www-acs.ucsd.edu/~idea/fossquotes.htm#insects 126- H.V.Daly, J.T. Doyen, and P.R. Ehrlich, Introduction to Insect Biology and Diversity, McGraw Hill, New York, 1978, sf. 274, 308 127- G..Giribet, G. D. Edgecombe & W. C. Wheeler, Arthropod Phylogeny Based on Eight Molecular Loci and Morphology. Nature, vol.413, 13 September 2001, sf.157 – 161 128- Zuhal Özer, Böcekler, Bilim ve Teknik, Şubat 2000, sf.95 129- Loren Eiseley, The Immense Journey, Vintage Books, 1958. sf. 227 130- Evolution, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, Vol. 93, August 1996, sf.8470–8474 |

8 / total 9

You can read Harun Yahya's book The Microworld Miracle online, share it on social networks such as Facebook and Twitter, download it to your computer, use it in your homework and theses, and publish, copy or reproduce it on your own web sites or blogs without paying any copyright fee, so long as you acknowledge this site as the reference.